Since Yemen descended into chaos almost a decade ago, the UN and the international community have struggled to negotiate a political settlement to the war. Yet, despite the passage of multiple UN Security Council resolutions and the establishment of the Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Yemen in 2012, there is precious little to show for these efforts. Yemen remains a country divided—not in half, but along a spider web of innumerable political and social fault lines. In 2020, the country had the second-highest number of people in food crisis in the world.1 Nearly a quarter of a million Yemenis have died because of the war.2

It should come as no surprise that the ongoing international efforts at peace-building have yielded so few successes. The international community’s strategy for mediating an end to the complex war in Yemen is fundamentally misguided. It relies on the delusional belief that a single, strong unitary state could somehow be revived to rule a unified Yemen. In reality, power in Yemen is divided between a dizzying array of actors. Some, like the Houthis and the exiled government of the president, Abdu Rabbu Mansour Hadi, are pretenders to state power. Others function as hybrid or nonstate actors, some armed and some civilian. Just as all are part of the conflict, all are likely to be part of a future peace. The sooner the international community and its mediators dispense with their Westphalian fantasies of a resuscitated Yemeni state, the sooner they can understand the reality of Yemen’s conflict—and craft a way forward.3

The idea that a Yemeni state could emerge from the ashes of the war and establish a monopoly over the use of force within its territory is based on several false assumptions. It fails to grasp the realities on the ground by overlooking the many nonstate armed actors that have evolved over the past six years, and which are now shaping local politics and the overall architecture of the conflict. Most of these groups not only operate entirely outside the control of the Yemeni government, but also compete with it. They have multiple local, sometimes fluid, agendas. Further, many of them operate with heavy influence from regional backers whose goals may not be aligned with the West’s aim of building a sovereign and functional national state in Yemen.

Recognizing and accepting Yemen’s fractured reality is critical for identifying alternative approaches that could support effective interventions to mitigate the war and to develop strategic and long-term policies to address regional security.

This report examines the array of nonstate armed groups that have emerged during the war—groups that are not included in the current UN-led negotiations in Yemen. In particular, the report looks at the main nonstate armed groups that were created by the United Arab Emirates in southern Yemen and on the country’s west coast. The analysis is based on interviews with eighty-two individuals, including twenty-four military and security officers, members of four armed groups, and dozens of local officials, political actors, tribal and community leaders, journalists, civil society leaders, and ordinary citizens. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, most interviews were conducted remotely. The author also consulted previous studies, including reports by the UN Panel of Experts on Yemen, the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED), news articles, and the social media feeds of armed group actors, political leaders, and activists. Most of the interviews cited in this report were conducted between 2019 and April 2021. However, the report also draws on the author’s twenty years of research in Yemen.

Learn More About Century International

The Importance of Hybrid Groups

A detailed catalogue of the armed groups operating just within the Emirates’ sphere of influence in the anti-Houthi camp attests to the complexity of the distribution of power in Yemen. It also shows the difficulty of establishing unified central leadership in the country. An accounting of these groups points to a future in which governance will have to mediate bottom-up factionalism as well as top-down, national-level political competition.

These hybrid groups will continue to have power even if the Emirates reduces its involvement. Eroded state structures, a civil war that is likely to continue for the foreseeable future, and the strong presence of competing national and foreign powers will sustain these actors. With a rapidly growing war economy, they will continue to solidify their local power and can always act as spoilers even if they cannot supplant the state. Yemenis who want to govern will have to find a way to co-opt or win the loyalty of these groups—or else will find themselves indefinitely engaged in low-intensity warfare. International mediators, similarly, cannot resolve Yemen’s war if they only address the national-level players; those national actors are simply too disconnected from the real local distribution of power.

A power-sharing agreement between the Hadi government and the Houthis will not stitch Yemen back together or give birth to a functional national government that can hold sway over existing armed actors. Even if representatives from these forces are brought to the negotiating table, it is unlikely they will be integrated under a national umbrella organization: national actors are the target of too much mistrust and too many long-standing grievances. These groups will likely retain their arms to maintain their leverage for any future political bargains.

A power-sharing agreement between the Hadi government and the Houthis is not going to stitch Yemen back together or give birth to a functional national government.

Nonstate armed actors are central to the conflict landscape, and the international community needs to reconstruct its understanding of this landscape accordingly. Hybrid groups can make or break peace-building efforts in Yemen.

Below, an overview of the trajectory of the war in Yemen shows how hybrid actors in the country proliferated—and how the on-the-ground reality has drifted far from the international community’s current framework for peace.

A Grueling Conflict

In February, Joe Biden appointed Timothy Lenderking as the U.S. special envoy to Yemen.4 With Lenderking, the administration intended to step up U.S. diplomatic efforts to end the war in Yemen, as Biden explained in a foreign policy address at the time of the appointment. “I have asked my Middle East team to ensure our support to the United Nations-led initiative to impose a ceasefire… and restore long-dormant peace talks,” Biden said, adding that Lenderking would work with the UN special envoy and all parties to the conflict to push for a diplomatic resolution. “This war must end,” Biden said.5

The Yemen war started in September 2014 when the Iran-backed Houthi rebels (also known as Ansar Allah), supported by forces loyal to former president Ali Abdullah Saleh, stormed the capital and overthrew the government of Hadi (then and now the president of Yemen). Soon after, the Houthis and Saleh’s forces launched a military offensive, capturing most Yemeni governorates, including the city of Aden in February 2015. Saudi Arabia formed a coalition, backed by the United States. In March 2015, the coalition launched a military offensive with the objective of reinstating the Hadi government.6 Six years later, with seemingly no end in sight, the war has caused Yemen to become the world’s worst humanitarian crisis. Two-thirds of the population needs humanitarian and protection assistance, and four million are internally displaced and living under dire conditions.7

Since 2014, the United States and the international community have supported the Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Yemen (OSESGY) in brokering a ceasefire and negotiating a political settlement between the Yemeni government and the Houthi rebels.8 In February of this year, UN special envoy Martin Griffiths shared his vision of an end to the war in a briefing he gave to the Security Council.9 The vision includes a negotiated agreement based on an inclusive partnership that ends the use of violence for political gain and culminates with national elections. “Security arrangements should provide for the Yemeni people’s safety and lead toward responsive security institutions that uphold the rule of law,” he said. In its 2018 “Integrated Country Strategy,” the State Department stated its long-term commitment to post conflict security sector reforms and disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration needs.10

Six years since the Saudi-led coalition was formed, the Houthi rebels have emerged as the strongest military force, while the Saudi-backed Hadi government has lost much of its influence throughout the country, including in areas that it claims to control. Incompetence, the absence of a military strategy, divergent agendas between Saudi Arabia and the Emirates (the other key member of the Saudi-led coalition), and a lack of Yemeni government leadership have all played into the hands of the Houthis.11

Incompetence, absence of a military strategy, divergent agendas between Saudi Arabia and the Emirates, and lack of Yemeni government leadership—all have played into the hands of the Houthis.

Lacking military capabilities, Saudi Arabia failed to organize an effective military offensive against the Houthis in the north.12 The Emirates was more directly involved in leading and managing ground military operations. It has created, trained, and equipped various local forces in the south and on the west coast of Yemen. These forces are at odds with the Yemeni government and some of them have been instrumental in undermining the government’s presence and control. These deficiencies and internal divides in the coalition further deepened political and regional divisions, again playing into the hands of the Houthi rebels.

In early 2020, the Houthis launched a major offensive, making substantial military gains. As of summer 2021, they are threatening to capture the city of Ma’rib, seventy-five miles east of the capital city of Sana’a. Almost 3 million Yemenis reside in Ma’rib, including over a million internally displaced people, and it is the last stronghold of the Yemeni government. So far, efforts to establish a ceasefire have failed to bear fruit. Most recently, Lenderking travelled to Oman and Riyadh (his sixth trip to the region since he was appointed in February). On these trips, he joined OSESGY and the five permanent members of the Security Council and held talks with key regional officials to push for a ceasefire. “We are not where we want to be in reaching a deal,” Griffiths said following the Oman tour.13

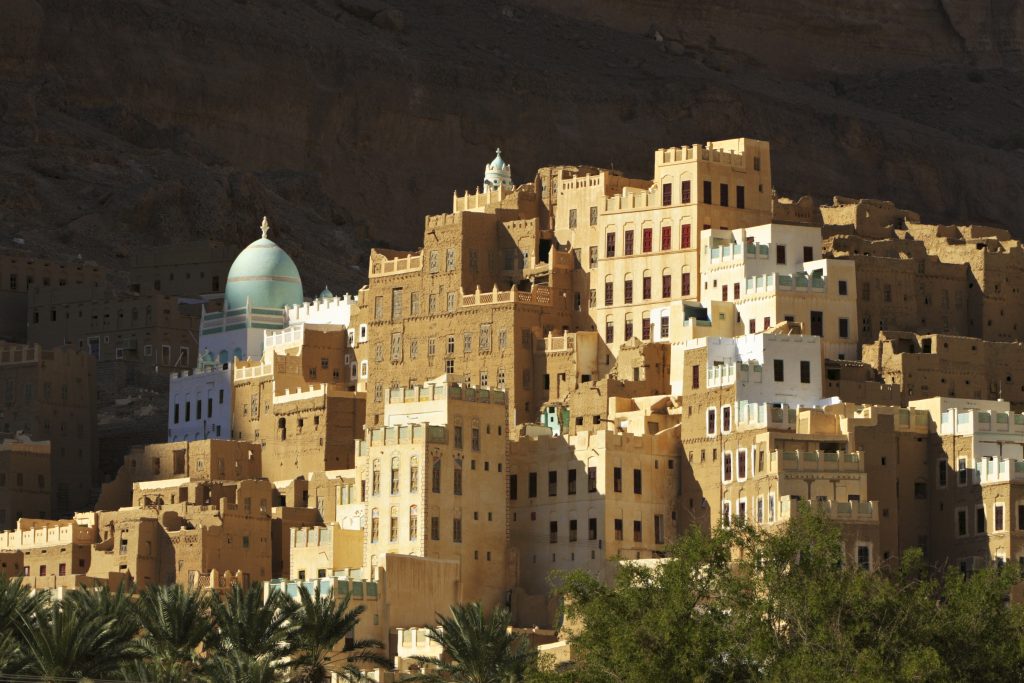

Most of the war in Yemen is characterized by low-intensity fighting across several fronts; overall, it remains a military stalemate. Geographically, Yemen has become divided along several lines: the Houthi-controlled northern areas; the government-aligned areas in the governorates of Ma’rib, northern Hadhramaut, Shabwah, al-Mahra, and Abyan, and in the city of Taizz; the separatist Southern Transitional Council (STC) in Aden and its surroundings; the west coast where the Joint Forces led by Tareq Saleh are the dominant force; and coastal Hadhramaut.14 This situation has resulted in the evolution of several “islands,” some dominated by armed actors with loose chains of command and fluid loyalties.

The Influence of the Emirates

Within the Saudi-led coalition, the Emirates has had the most impact over the course of the conflict since 2016. Emirati forces played a key role in pushing the Houthis out of the south in 2016 through direct military engagement and support to the southern resistance forces that rose in response to the Houthi incursion into the area. Ever since, the Emirates has built a strong influence in the south and the west coast of Yemen, where it has created, trained, and commanded forces that operate entirely outside the Yemeni government chain of command. It is responsible for creating armed actors with incoherent ideologies and weak cohesion that clashed with the Yemeni government, and which have contributed to dividing the anti-Houthi camp—divisions that have given military advantages to the rebel group.

Despite scaling down its military presence in late 2019, the Emirates still has substantial influence in Yemen.15 The Emirates still controls key ports, including the seaport of Balhaf in Shabwah governorate, which hosts Yemen’s largest economic facility (where Yemen’s natural gas liquefaction project, YLNG, exports gas and oil), and Mukalla’s seaport in Hadhramaut.16 Abu Dhabi also retains a heavy military influence on Socotra Island, and is building an airbase on Perim Island in the strategic international strait of Bab al-Mandab in the Red Sea.17 More recently, the Emirates has switched from direct to indirect engagement by recruiting, training, and equipping 200,000 Yemeni soldiers and security forces members.18 Abu Dhabi has sustained its influence through increased reliance on local proxies and partners, as Yemeni analyst Ibrahim Jalal has argued. 19

The Emirates’ intervention in Yemen is guided by Abu Dhabi’s larger strategic vision of asserting itself as a military and economic power in the region. In Yemen, it is also driven by its desire to exterminate Islah, a prominent Yemeni Islamist political party that is loosely affiliated with the Muslim Brotherhood, which the Emirates considers a terrorist organization.20 “We were fighting three enemies at the same time: the Houthi coup, the Muslim Brotherhood and their fifth column, and al-Qaeda and Daesh [Islamic State] terror,” said Eisa Al Mazrouei, the Emirates’ deputy chief of staff, addressing top political and military leaders in a ceremony commemorating the withdrawal of Emirati forces from Yemen in February 2020.21

The Emirates’ desire to undermine Hadi’s government can be explained by its belief that Hadi is heavily influenced by Islah. Its fears might have been reinforced when, in April 2016, Hadi removed former vice president Khaled Bahah, a figure who is close to the Emirates, and appointed Ali Muhsin al-Ahmar, a main supporter of Islah, as a replacement. To build a counterforce, the Emirates has created and supported an array of political, religious, and armed actors who do not necessarily have common goals with each other but share deep resentment for Islah, the Hadi government, or both. The political polarization and disintegration of the Yemeni army, particularly in the south, led other forces that are affiliated with the government to ally with Emirates-backed factions.

Yemen’s South

While the Emirates formed and supported various armed groups in the south and on the west coast, it also supported two Yemeni actors who have become something of a political umbrella for these armed groups. These actors are the STC in the south and Tareq Saleh (the nephew of former president Ali Abdullah Saleh) on the west coast. Although Emirati funding and supervision—along with common goals and enemies—helped establish this order, there remain fundamental differences between these groups. The factions have set these differences aside for the time being, but they will likely resurface when circumstances change. A detailed description of these groups and their aims and origins is essential to understanding the contours of the conflict in Yemen and its possible outcomes.

The Southern Transitional Council

The STC is one of the largest and most important Emirates-affiliated factions in Yemen today, with tens of thousands of fighters and a political machine with powerful influence throughout the south of the country. Even if it never realizes its goal of an autonomous southern Yemen, it will be a force to be reckoned with in Yemen’s future.

In May 2017, the STC was formed with strong support from the Emirates. The STC’s stated goal is the secession of southern Yemen from the rest of the country—a return to something like the borders that existed before the 1990 unification of the Yemen Arab Republic (North Yemen) and the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY, or South Yemen). Armed forces operating in Aden that were created by the Emirates affiliated themselves with the STC soon after the latter’s creation; these factions included, among others, the Security Belt Forces, counterterrorism forces, and even the Aden Security Directorate (the police force that formally falls under the command of the Ministry of Interior).

Even if the Southern Transitional Council never realizes its goals of an autonomous southern Yemen, it will be a force to be reckoned with in Yemen’s future.

The STC and allied forces are predominantly from the southern regions of Yafa’a and Dhale, while forces loyal to Hadi, including the Presidential Protection Brigades commanders and members, are mainly drawn from his home governorate of Abyan. A division along regional lines (Yafa’a and Dhale versus Abyan and Shabwah) is rooted in the power struggle among former leaders of the PDRY that led to a bloody civil war in 1986—a conflict that remains largely unresolved today.

Tension between the STC and allied forces on one side and the Hadi government on the other rose in early 2017 and continued to escalate during the following years. A series of clashes eventually led to the expulsion of the Yemeni government from the south in August 2019.22

Saudi mediation and pressure led the Hadi government and the STC to sign the Riyadh Agreement in November 2019, which aimed to form a new government that includes the STC; to disarm and integrate militaries and military formations under Yemen’s Ministries of Defense and Interior; and to demilitarize the city of Aden. But after more than a year of stalled negotiations, none of the items in the agreement have been implemented except the formation of the new cabinet. As a result, and despite relocating to Aden, the Yemeni government remains largely at the mercy of the STC.23

Forces Affiliated with the STC

Between 2016 and 2018, the Emirates created several forces in southern Yemen, many of which became loosely affiliated with the STC following the expulsion of the Yemeni government from Aden in August 2019.

These forces created by the Emirates bonded over shared interests and common enemies, rather than political loyalty. In September 2018, STC vice president Hani Bin Buraik said that the STC did “not have any armed forces affiliated with it,” a claim repeated by other STC officials. The lines of command operate by parallel and informal means rather than an established structure of command and control.24 Southern forces are currently working with the STC because they fear a Houthi revanche in the south, and because of the need to stop a perceived Islah incursion into Aden under the banner of Hadi’s government forces.

In Aden and the surrounding governorates of Lahij and Dhale, these forces exist as units that operate independently of each other and from other units, with no unified command. Because they are drawn mainly from Dhale and Yafa’a, they were dragged into the power struggle between Hadi and the STC. The role of the Emirates is key to keeping these forces in check and maintaining their alliance with the STC. Absent structure and discipline, clashes among these forces are common, sometimes affecting civilians and civilian property. For example, in March 2020, clashes between the Security Belt Forces and the Special Forces in Aden left one soldier dead and three injured.25 In June 2020, clashes erupted between the Thunderbolt Brigade under Awsan al-Anshali and the Security Belt Forces under Imam al-Noobi.26

In Hadhramaut, Shabwah, and Abyan, local armed forces are mostly driven by local priorities rather than political agendas. They desire to be formally enlisted by the government as local security forces operating in their governorates. Still, they remain at the mercy of the current conflict in the south.

For example, when tensions escalated following the STC’s eviction of the Yemeni government from Aden in August 2019, one nominally government-aligned faction, the Shabwani Elite Forces (SEF), initially stood down because the fighting was outside its mandate, which was mainly basic security. But the group gradually got caught in the power struggle between the Yemeni government and the STC. The STC then attempted to deploy the SEF to fight government forces in Ataq, the capital of Shabwah. The SEF was forced to withdraw two days later, after government forces launched a counteroffensive.27 The SEF diminished, including in its role as a security actor, after government forces regained control of the governorate. The SEF was relocated to Aden in late 2019, but reportedly remained marginalized and dominated by security leaders, mainly from Dhale and Yafa’a, running other security forces in Aden.28 A month after the SEF’s relocation, eighteen members of the group were arrested by the STC-allied Thunderbolt Brigade after protesting delays in their salary payment.29 In March of this year, the commander of the SEF resigned from his position.30 These events occurred in the context of the decades-old political rivalry, mentioned above, between Shabwah and Abyan in one camp and Dhale and Yafa’a in the other.

Another example of the complicated command structures and shifting allegiances of these groups involves the Security Belt Forces in Abyan governorate. There, the Security Belt Forces picked up arms and fought with the STC to stop government forces from taking Abyan in 2020. By contrast, in Hadhramaut, the Hadhrami Elite Forces (HEF) maintained a local mandate focusing on security functions. Although the HEF is not as hostile to the Yemeni government as some of the other STC-affiliated groups, it reports more to the governor of Hadhramaut than to Yemen’s Ministry of Interior. Historically, Hadhramis have taken pride in their distinct identity and are eager to establish autonomy under any future settlement.31 They reject the authority of the elite that ruled Hadhramaut from Sana’a in the past, and now from Aden. Hadhramaut has also been far from the direct confrontations that took place in other southern governorates.

Descriptions of some individual STC-aligned fighting forces give a more detailed sense of the tangled web of allegiances and command lines in the country.

The Support and Backup Brigades and the Security Belt Forces

The Support and Backup Brigades (SBB) and the Security Belt Forces are the most influential armed groups that have emerged during the war. Their fighting against the Yemeni government has shaped the conflict dynamics in the south—even as they are also formally recognized by the government. These two forces began clashing with Yemeni government forces in Aden in 2017 and eventually helped drive the government out of the city in August 2019, an event that led to significant instability in southern Yemen.32

The SBB was created by the Emirates in Aden in March 2016 to fill the security vacuum in the city after the Houthis were pushed out.33 The Security Belt Forces is a subgroup of the SBB. The two groups’ main activities have been to man checkpoints in Aden, such as the key al-Alam checkpoint connecting Aden to neighboring governorates. In May 2016, Hadi issued a decree officially forming four SBB groups as a military unit under the command of the Ministry of Defense.34 Technically, the decree put the SBB under the direct command of Yemen’s Fourth Military Region (a Yemen Armed Forces administrative area). In reality, the SBB and the Security Belt Forces operate entirely outside the government’s command—and have since their inception.35 Further, as early as the end of 2016, the Security Belt Forces refused to take orders from the Yemeni government.36

There is no official figure for the number of SBB and Security Belt Forces fighters, but they are estimated to have a combined 15,000 members, who operate through most of southern Yemen, mainly in Aden, Lahij, Abyan, and Dhale.37

First Mountain Infantry Brigade

Despite officially being part of Yemen’s Ministry of Defense, the First Mountain Infantry Brigade’s almost 3,000 soldiers come mainly from Dhale and were handpicked by its commander, Aidaros al-Zubaidi, president of the STC. Hadi formed the brigade through presidential decree in late 2015, around the same time that he also appointed Zubaidi as the governor of Aden. Gifting military units and brigades to obtain loyalty is a common practice in a country where the military has largely operated as a wide patronage network. Despite its official standing, the First Mountain Infantry Brigade operates outside the Ministry of Defense chain of command and is under Zubaidi’s direct control. The force received funding and training from the Emirates.

Despite its official standing, the First Mountain Infantry Brigade operates outside the Ministry of Defense chain of command, and is under Zubaidi’s direct control.

The brigade is located on Jabal Hadeed, a mountain that overlooks all the neighborhoods and the seaport of Aden, and is the prime strategic location in the city. It has a large stock of weapons, most of which were looted from army camps in the years before the war. This brigade guarantees the personal security of Zubaidi, STC members, STC premises, and its members’ homes. With direct funding from the Emirates, the brigade has its own independent budget and administration. 38

Forces of the Fourth Military Region

Perhaps the most notable development during the current war in Yemen has been the de facto defection of the Fourth Military Region. Based in Aden, the region’s command is one of seven military regions under Yemen’s Ministry of Defense that run military operations in the governorates of Aden, Taizz, Lahij, Abyan, and Dhale. When the STC and allied forces drove out the Yemeni government in August 2019, some army commanders and officers with roots in the south began to lose their trust in the leadership of the Yemeni military. With the STC asserting its control, many felt that the Yemeni government had no future in the south. For example, following the August 2019 development, the Fourth Military Region’s commander Fadhl Hassan pledged allegiance to the STC; he commands a force of 5,000 soldiers.

The Fourth Military Region also includes al-Anad Airbase. With some 5,000 soldiers, al-Anad is the Yemeni government’s largest air force camp. The camp and soldiers are organized under Yemen’s Ministry of Defense. After the events of August 2019 that culminated in the government’s expulsion from Aden, camp commander Thabet Jawas declared his support for the STC and southern secession.39 He also declared support for the STC’s decision to govern southern Yemen autonomously, in yet another development that undermined the central government’s presence in the south.40

Losing the loyalty of the Fourth Military Region was a major blow to the Yemeni government. In a June 2020 meeting with members of the parliament, Yemeni prime minister Maeen Abdulmalik Saeed said that 55 percent of Ministry of Defense salary allocations went to the Fourth Military Region. From that budget, the region’s commander—Hassan, who has professed loyalty to the STC—earns a staggering monthly salary of 25 million Yemeni rials (about $42,000). The monthly budget for the region is about 15 billion Yemeni rials (about $25 million), to account for salaries for troops and operational costs. 41

Security Belt Forces in Abyan

Abdul Lateif al-Sayid leads the Security Belt Forces in Abyan. Sayid formerly led the Abyan Popular Committees that spearheaded the fight against al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) and pushed the extremist group out of Abyan in 2012.42 The force numbers about 2,000 members, many of whom are former Popular Committee members, all from Abyan.43

Members of the Popular Committees were initially loyal to Hadi, but Hadi alienated its members when he failed to incorporate them into Yemen’s formal security forces after the committees defeated AQAP in 2012. The Popular Committee members remained without salaries or support from Hadi’s government, and hundreds of them were killed in AQAP attacks. Sayid himself has survived seven assassination attempts and lost three of his brothers in AQAP attacks.44

In February 2017, Sayid was appointed as the commander of the Security Belt Forces in Abyan. The force led by Sayid had the goal of carrying out counterterrorism operations and managing security in the governorate.45 This force allied itself with the STC following the Yemeni government push in Abyan in 2019—a push that many perceived to be controlled by Islah. But the Security Belt Forces remains largely apolitical, and members are mainly motivated by the prospect of enlisting in a formal security force and defending their areas against extremist groups that are still actively targeting them.46

The Elite Forces

There are multiple groups calling themselves “Elite Forces” that continue to play a role in the conflict in Yemen. All are tied to the Emirates to some degree. Some, like the SEF, operate under Emirati command, while others, including the HEF, operate directly under local authorities.

The Emirates created the HEF in April 2016, in coordination with the Yemeni government and local Hadhrami tribes, ahead of a planned assault to push AQAP from Mukalla. Members were recruited from local tribes; they now number 30,000.47 The forces currently operate under the command of Faraj Salman Al Bahsani, governor of Hadhramaut and commander of the Yemeni government’s Second Military Region. (The Emirates reportedly brought back Al Bahsani from his twenty-year exile in Saudi Arabia and Egypt and asked Hadi to appoint him to his current position.) Although the HEF is technically organized under the Ministry of Defense, the force has, in practice, operated under the direct supervision of the Emirates and outside of the Yemeni ministry’s chain of command.48 The United States continues to provide logistical support, including air support, to the HEF.

The SEF was formed by the Emirates in mid-2017. It deployed in Shabwah in August of that year, manning checkpoints on the highways between Mukalla and Ataq, and between Ataq and Abyan. The SEF is divided into four units of about 3,000 members, with each unit’s members coming from a specific tribe. Its members were recruited through tribal and community leaders, and trained by Emirati officers.49

The HEF and SEF have also carried out counterterrorism operations and security functions, each within its governorate, under the direct command of the Emirates.

The Emirates created another group, the Mahri Elite Forces, in 2015 by recruiting about 2,000 members from local tribes. But the Mahri Elite Forces eventually disbanded because of a lack of local support.

Yemen’s Tihama Coast

Yemen’s western littoral, the Tihama Coast, is home to the country’s most important seaports. The port of Hodeida is the entry point for most commercial imports and humanitarian aid; the port of Ras Isa is the terminus of Yemen’s main oil pipeline. Ports at Mocha and Midi are other notable harbors; they respectively mark the southern and northern ends of the Tihama Coast.50 The ports are currently controlled by the Houthis and an array of Emirates-backed forces.

In December 2017, Emirates-backed forces launched an offensive to take control of several key sites from the Houthis on the Tihama Coast, south of the city of Hodeida.51 The operation continued into 2018; in June of that year, troops rapidly advanced into the southern outskirts of Hodeida, preparing to storm the city.52 The fighting paused in July 2018 after pressure from the UN and major outside powers, who warned of the potential of widespread famine if Yemen’s main port was besieged. During this lull, the Saudi-led coalition agreed to give OSESGY (the UN special envoy’s office) an opportunity to negotiate a political solution.53 Military operations temporarily halted when parties agreed to a ceasefire under the Stockholm Agreement brokered by OSESGY in December 2018. However, fighting continued around Hodeida, and implementing the Stockholm Agreement has proven to be a tremendous challenge in an extended political and military stalemate.

To carry out its military operation, the Emirates constructed several armed groups (described below) and brought them under the umbrella of the Joint Forces in July 2019.54 A Joint Operation Room was formed for the Joint Forces and is directly linked to the Saudi-led coalition on the west coast.55 The Joint Leadership is led by Staff Major General Haitham Qassim Tahir, who served as the first minister of defense after Yemen’s unification in 1990. This leadership body is designed to be a roundtable that includes representatives from the different forces on the west coast. However, Tareq Saleh—the nephew of former president Saleh—is actually the key figure and decision-maker in the Joint Forces, second only to the coalition. 56

Forces on the west coast are unified around the goal of defeating the Houthis. But their specific agendas differ —and have the potential to diverge more drastically in the future.

Forces on the west coast are unified around one goal, which is to defeat the Houthis and prevent them from making more military advances in the region. Their agendas, however, differ —and have the potential to diverge more drastically in the future. One group, the Guardians of the Republic, has a national agenda and are driven by a desire to liberate the west coast, and eventually the entire north, from the Houthis. Their chief ambition is for Saleh’s family and the former president’s political party, the pan-Arab General People’s Congress (GPC), to regain the influence they lost when Saleh was ousted in 2011.

Disagreements run deep within the Joint Forces, despite their unified structure. While the Tihama and Al-Zaraneeq Brigades—which are composed of locals from Hodeida governorate—share the goal, with Tareq Saleh’s Guardians of the Republic forces, of removing the Houthi threat, they are ultimately driven by deep and long-standing grievances against the national political elite. In the longer-term, they are seeking to end the political marginalization of the Tihama Coast, empower their people, claim their fair share of resources, and govern their areas autonomously within a federal system.57 This may put the Tihama and Al-Zaraneeq Brigades at odds with Tareq Saleh’s forces in the future. Tensions have risen, in fact, because the Tihama Brigades were annexed into the Guardians of the Republic and the Giants Brigades (described below), relegating the former to a subordinate status. This annexation came in response to a lack of professionalism among Tihama Brigades fighters. But whatever the reason, the move deepened existing resentment and grievances among Tihamis.

In response to the consolidation of power in the hands of Tareq Saleh, a series of protests occurred in the city of al-Khokha on the west coast in 2019 and 2020. Armed disputes between the Tihama Brigades and Guardians of the Republic erupted early this year, underscoring, as Ibrahim Jalal has written, “the ongoing tension, discontent, and suspicion as to Tareq’s intentions.”58

Below, I provide a more detailed look at the factions on Yemen’s west coast.

The Guardians of the Republic

The Guardians of the Republic was founded by Brigadier-General Tareq Saleh in 2018, and was first known as the “National Resistance.” Tareq Saleh was the commander of the Private Guard of Saleh (the former president) and the Third Brigade of the elite Republican Guard forces until he was sacked by Hadi in 2012. Although not politically active, Tareq Saleh is closely aligned with the GPC abroad, which is loyal to the family of the former president and affiliated with the former president’s son, Ahmed Ali. Tareq Saleh is a natural opponent of Hadi and Islah, whom GPC supporters blame for removing the elder Saleh from power in 2011, and for removing his family from key military and political positions in the years to follow, as well as an assassination attempt on the former president that same year.59

Tareq Saleh and his supporters feel they have been marginalized by Hadi and Islah, who now control the government. Tareq Saleh has been trying to assert himself and his group as a military and political power. On March 25 this year, in anticipation of a political settlement, Tareq Saleh declared the formation of a political entity to represent his forces, which he called the Political Office for National Resistance.”60 Most members of this force have a military background. In particular, most were part of the former Republican Guard forces led by Ahmed Ali, before those forces were dismantled during the transition process following the former president’s removal and the war that followed.

The Guardians of the Republic operates entirely outside the Yemeni government’s chain of command. It recognizes the Yemeni government, but distrusts it, according to a Guardians of the Republic source, because it perceives the government to be controlled by Islah, which—as described above—is a political rival to the GPC and the Saleh family.61 In Tareq Saleh’s speech launching the Political Office, he indicated that his forces do not seek to replace the Yemeni government; rather, they want to be part of it.62 Still, though the Guardians of the Republic may not be against the government, its position indicates that it will demand a large share of government posts and power in the future.

Nevertheless, there is a level of cooperation between Tareq Saleh’s forces and the Yemeni government. For example, the Special Forces and Public Security units for Hodeida (a police force), which are part of the Yemeni Ministry of Interior, receive salaries from the government of Yemen and logistical support and food supplies from the Guardians of the Republic. In some instances, Tareq Saleh has paid this police force’s salaries when they were delayed.63 The Guardians of the Republic also works on the Yemeni government side to implement the Stockholm Agreement. For example, Sadeq Duwaid, who is a member of the Joint Forces and Guardians of the Republic, is also part of the Yemeni government’s team in the Redeployment and Coordination Committee that was established under the Stockholm Agreement.64

The Giants Brigades

The Giants Brigades is the largest force under Emirati command on the Tihama Coast. It was instrumental in liberating key west coast sites from the Houthis, including Bab al-Mandab, Dhubab, Mocha, and parts of Hodeida. The Emirates began recruiting for the Giants Brigades in 2015.65 The force has grown into thirteen brigades comprising 20–28,000 fighters.66

Most Giants Brigades commanders are Salafi leaders who graduated from the Dammaj Salafi Institute in Saada; some fought the Houthis during the Saada wars. However, the vast majority of its members are ordinary southerners who come mainly from the southern governorates of Aden, Abyan, Dhale, Lahij, and from the areas of Yafa’a and Sabayhah, and were drawn from those who previously fought the Houthis in 2015. They have no ideological or political motive apart from preventing the Houthis from returning to the south and the stable source of income the membership in the Giants Brigades affords. Most fighters are motivated by financial incentives. The salaries that Giants Brigades members receive have transformed their areas economically. For example, in Karish, in the district of al-Musaymir, and in Sabayhah in Lahij, people’s lives have improved dramatically as a result of the salaries that Giants Brigades members receive and send home. “Now they have houses instead of hay huts,” a local resistance fighter said. “They own cars and young men are able to get married. These areas are extremely poor, and the salaries of the fighters made a huge difference in people’s lives.”67

Of the group’s thirteen brigades, only the first three were officially formed by republican decree in January 2018. The rest of the brigades were formed outside the government of Yemen. In October 2019, the Emirates relocated about a third of Giants Brigades forces to the south to back up STC fighters against Yemeni government forces in Abyan. Some of these forces were also relocated to the Dhale front line after the Houthis made gains in Qa’atabah, in the north of the governorate, in early 2019.68

Tihama Resistance Forces

The Tihama Brigades and the al-Zaraneeq Brigades are the only two forces that were formed by the Emirates on the west coast that are composed entirely from local Tihamis who come from the governorate of Hodeida—a region that historically has been marginalized and oppressed by the central government.

The two forces were formed during 2017 as part of the Emirates’ effort to push the Houthis out of the west coast. They were drawn from local resistance forces that formed during 2014 and 2016 to stop the Houthis’ incursion into Hodeida governorate. Some also came from al-Hirak al-Tihami, a peaceful movement that emerged in 2011 in the wake of the Arab uprisings to demand an end of the oppression and exploitation of the Tihama people by the Sana’a regime.69 The 6,000 fighters of the Tihama Brigades are divided into four brigades.70 The smaller Al-Zaraneeq Brigades took its name from the once-powerful Al-Zaraneeq tribe, to which most of the force’s members belong. The tribe fought against oppression by the imamate—a theocratic system that ruled parts of northern Yemen for hundreds of years until it was overthrown in 1962, though the imam was not able to control Tihama and subjugate the Al-Zaraneeq tribe until 1929.71

Many of the individuals who joined these forces were students who were unable to finish their education, or individuals who lost their jobs or salaries as a result of the war—including teachers, health workers, and unemployed people. “The salary is a thousand Saudi riyals and food supplies,” a journalist from the Tihama Coast said. “It’s good money. These young men feed families and sometimes use the food they receive from their brigades to feed their neighbors and poor people.”72

“The salary is a thousand Saudi riyals and food supplies,” said a local journalist. “It’s good money. These young men feed families and, sometimes, their neighbors and poor people.”

Because they were smaller and less professional forces, the Tihama and Al-Zaraneeq Brigades were incorporated into the Guardians of the Republic and Giants Brigades. This move angered some Tihama resistance and political leaders who saw it as a continuation of the subjugation of Tihamis. Most notably, this reorganization led to a power struggle between Ahmed al-Kawkabani—the commander of the first Tihama Brigade—and Tareq Saleh, which manifested itself in tensions and, occasionally, armed clashes. Kawkabani is said to be affiliated with the Islah party, a longtime rival of Saleh supporters, which further complicates the situation. In 2019, Kawkabani refused to hand over the security and government facilities in his hometown, the coastal city of al-Khokha, to the new governor, whom he viewed as being controlled by Tareq Saleh. In July 2020, he deployed his armed men on pickup trucks in front of the Security Directorate and Civil Affairs Authority in al-Khokha to prevent the local authority from taking over these forces. A local journalist said that Kawkabani is described as the “true ruler of al-Khokha.”73

Most of the Tihama Brigades fighters accepted their incorporation into the Guardians of the Republic and the Giants Brigades, because their salaries were now dependably paid by Tareq Saleh. But the grievances between Kawkabani and Tareq Saleh are unlikely to be resolved if the Tihama Coast’s people are not represented in future security and governance structures. “Tareq has the money, and he can pay salaries so [Tihama Brigades’ leaders and members] accepted his leadership, because that is the only option they have now,” said a senior member of the Tihama National Council, a political body that advocates for the empowerment and better representation of Tihamis. “But tomorrow is another day,” he added, indicating that Tihamis will continue to demand to govern their own areas. “A hundred years of marginalization is not going to go away easily, but we won’t give up,” the council member said.74

Perceptions of the UN-Led Negotiations

In a briefing to the Security Council on May 12, Martin Griffiths, the UN envoy to Yemen, described strong “international backing” for UN goals in Yemen, including a nationwide ceasefire and an “elusive” political settlement. “There is regional momentum for the UN’s efforts,” he said.75

On the ground in Yemen, however, feelings about the international community’s efforts are quite different. There is strong distrust of the current UN-led negotiations among hybrid groups that are now in control of about 70 percent of Yemen’s geography and almost all its strategic facilities, including key seaports and airports. In the south, forces do not recognize the Houthis or Hadi’s government. In March 2019, the STC warned that the exclusion of the south from the UN peace talks would trigger new conflict.76 This sentiment is shared by the armed groups affiliated with the STC in the south. Both in the south and on the west coast, armed groups widely believe the peace negotiations directly or indirectly benefit the Houthis at the expense of the rest of Yemen.

On the west coast, forces believe that the Stockholm Agreement that was brokered by the UN envoy in December 2018 helped the Houthis reposition their forces to launch more aggressive offensives and make significant military gains. On several occasions, Tareq Saleh called upon the Yemeni government to withdraw from the Stockholm Agreement, describing it as a “conspiracy” against the state, the republic, the people of Yemen, and the security of the region.77 “The Stockholm Agreement lost its political and humanitarian justifications after it became a cover for Houthi militias to continue to target villages, homes, and farms of people and the locations of the Joint Forces,” said Tareq Saleh during a field visit to some of his forces in May 2020.78 His view is shared by all hybrid actors described in this report.

“The Stockholm Agreement lost its political and humanitarian justifications after it became a cover for Houthi militias to continue to target villages, homes, and farms of people and the locations of the Joint Forces,” Tareq Saleh said.

Members of the Joint Forces complain that they were not represented in the discussions that yielded the Stockholm Agreement, even though they were the ones doing the fighting on the ground. A senior member of the Guardians of the Republic said that despite not formally recognizing Hadi’s government, the group tried to help implement the agreement and even assisted the UN Redeployment Committee because it wanted to peacefully resolve the conflict on the west coast. However, he and other leaders interviewed complained that the Houthis continue to violate the ceasefire, launch attacks on civilians and the Joint Forces, and lay landmines that kill civilians—but the UN fails to hold the rebel group accountable.79

A senior member of the Joint Forces said that the fact that the UN monitoring team resides inside a Houthi-controlled zone in Hodeida—where the team is subject to strict Houthi rules on its movement—undermines the team’s neutrality. The member explained that the Joint Forces had repeatedly asked the UN to change the premises of the monitoring team, to no avail. The Joint Forces proposed turning the unused airport of Hodeida—which is located between the Houthi and the Joint Forces areas of control—into a green zone and to even allow flights to come into the city. But the Joint Forces said that its proposal received no traction from the UN Special Envoy’s office.80

Hybrid groups have established themselves as an important feature of Yemen’s conflict landscape. They can undermine and even obstruct the implementation of any political agreement that does not include them.

The Way Forward

The catalogue of armed groups presented above, including the context of their motivations and incentives, reveals the limitations facing the current international approach to ending the conflict in Yemen. This effort remains narrowly focused on fixing national-level politics through power-sharing agreements among the national elite as a foundation for reconstructing a central authority. But this approach neglects the second-order effects of the war, particularly the ascendancy of hybrid groups in Yemen’s politics—groups that have overshadowed a collapsed and increasingly irrelevant state.

The armed groups described in this report will likely continue to wield local power and compete with provincial and national governments, even if the Emirates reduces its involvement in Yemen. The groups’ emergence is the result of a combination of factors, including power struggles between actors at the national and subnational levels, competing perceptions of the social contract and shape of the Yemeni state, long-standing grievances, and a cycle of exclusion that the current UN-led peace negotiations have reinforced. As a result, Yemenis who want to govern will have to find a way to co-opt or win the loyalty of these armed groups—or else will find themselves indefinitely engaged in low-intensity warfare

The current circumstances are not conducive to reinstating a central government that can hold authority over all these armed groups. Attaining peace and building the state in Yemen will not be achieved through a political settlement between the Hadi government and the Houthis. In fact, such a settlement would likely cause more disintegration, as armed actors who feel left out resort to violent ways to assert themselves. The international community needs to think of realistic and practical ways to help Yemen—and be prepared to invest for the long term. To reverse the cycle of fragmentation, the question of hybrid actors must be addressed. If hybrid actors are not supervised, they may become predatory and evolve into a significant security problem.

As part of its support for the peace process, the international community should consider supporting interventions and programs targeting hybrid actors in a way that promotes their role in security provision. At the same time, interventions should develop mechanisms that link hybrid actors to civilian authorities and hold those actors accountable for their actions. This report offers the following suggestions:

- Acknowledge reality. International mediators cannot mitigate Yemen’s war if they only address the national-level players; those national actors are simply too disconnected from the real distribution of power on the ground, as this report’s analysis of the Emirates’ sphere has shown.

- Top-down political settlement will backfire. Do not impose a political settlement between Houthis and the Hadi government. Such a forced settlement will likely be counterproductive. Instead, the international community should lower its expectations, determine what it can realistically do to mitigate the conflict, and be prepared to sustain its engagement in Yemen for the long term.

- Bring regional actors into the conversation. It is impossible to address the issue of armed groups without engaging their sponsors. Saudi Arabia and the Emirates should be engaged in a discussion on ways to incorporate hybrid actors into future security structures. Hybrid actors can become more positive players—and their potential to act as spoilers will be minimized—if regional powers use their leverage to influence the hybrid actors’ behavior. At the same time, regional actors can help ensure that local grievances are addressed, and that hybrid actors have avenues to pursue their legitimate aspirations through negotiated agreements.

- Understand and engage hybrid actors. The lack of representation of hybrid actors in the peace negotiations must be addressed no matter the outcome or shape of future talks. As long as the international community has no relationships with such groups, it will be hard for the international community to understand them or influence their course of action. Humanitarian and development actors and local and international aid organizations have experience engaging with these hybrid actors and negotiating access with their commanders. Such organizations can offer valuable insights to the UN and international actors involved in the peace process about the nature and dynamics of these armed groups.

- Support political and peaceful actors. The international community should be cautious: it should not engage hybrid actors in a way that incentivizes their violence or sidelines political and peaceful actors. The international community should support interventions and programs that bring in more peaceful local actors that are currently excluded from the peace negotiations. These actors include local authorities that have established legitimacy at the local level, civil society groups, political associations that represent marginalized regions such as the Tihama National Council, and others. Such groups and individuals should be participating in discussions about Yemen’s future.

- Take a localized approach for better security governance. Rather than focusing only on national politics, a localized approach would be more appropriate and effective to building peace and improving security in the long term. In the absence of a negotiated agreement, the international community can focus on improving the professionalism of hybrid actors while ensuring they are held accountable for their actions. While each local context should be assessed separately, hybrid actors should be encouraged, as much as possible, to integrate into formal governance structures. The international community can assist in this goal by closely channeling or coordinating support with the Yemeni government or local authorities at the regional or governorate level.

- Strengthen accountability measures. Hybrid actors that have a strong ideological orientation and are involved in systematic and grave violations of human rights should not be supported. The international community should instead support those groups that are interested in upholding rights, providing incentives to encourage accountability, especially through programs that build the capacity of these groups to uphold existing, but often ignored, Yemeni laws governing security, international law, and the protection of civilians. To this end, the international community should consider funding programs that promote dialogue between hybrid actors and communities in which they operate. Programs should support civil society organizations, journalists, and media outlets that are active in documenting and exposing violations of human rights by armed actors.

- Explore options for demobilization. Many members of hybrid actor groups both in the south and on the west coast joined these forces mainly because they hoped to eventually be enlisted in formal security forces, because the security sector offers a stable source of income. Others were simply motivated by stipends and allowances. The international community can use these motivations to assist with demobilization—by funding and developing programs that create other income opportunities—and thus help reintegrate fighters into civilian life.

The current internationally sanctioned peace process is limited and flawed. The proposals above provide alternatives that will allow the international community to help Yemen by engaging hybrid actors, which are an important element of the conflict landscape. These recommendations should be pursued cautiously, and are not meant to suggest that the international community should normalize relations with hybrid actors. But at the very least, these interventions can improve local security and accountability, which will help mitigate the impact of the conflict on ordinary Yemenis. In the long run, such incremental achievements can also create demands for peace and establish foundations for governance structures that will bring much needed stability to the country.

This report is part of “Transnational Trends in Citizenship: Authoritarianism and the Emerging Global Culture of Resistance,” a TCF project supported by the Carnegie Corporation of New York and the Open Society Foundations.

header photo: Fighters with the forces of Tareq Saleh Forces man an outpost near the frontline in Al-Himah, Yemen, in September 2018. Source: Andrew Renneisen/Getty Images

Notes

- “2021 Global Report on Food Crises,” World Food Programme (WFP), 2021, https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP-0000127343/download/?_ga=2.32566142.1545674652.1623358889-1917663228.1621821120.

- “Un Humanitarian Office Puts Yemen War Dead at 233,000, Mostly from ‘Indirect Causes’,” UN News, December 1, 2020, https://news.un.org/en/story/2020/12/1078972.

- The author wishes to thank Ibrahim Jalal for the peer review of earlier drafts and Ahmed Al-Ashwal for assisting with the field research. Special thanks to Thanassis Cambanis and Eamon Kircher-Allen for the feedback and editing of the report,

- “Timothy A. Lenderking,” U.S Department of State, https://www.state.gov/biographies/timothy-a-lenderking/.

- MSNBC (@MSNBC), “Live now on @MSNBC : President Biden makes foreign policy address,” Twitter, February 4, 2021, https://twitter.com/MSNBC/status/1357424207999737871?s=20.

- For an in-depth discussion of Yemen’s political transition and interventions to end the conflict see Nadwa Al-Dawsari, “Breaking the Cycle of Failed Negotiations in Yemen,” Project on Middle East Democracy, May 2017, https://pomed.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/PolicyBrief_Nadwa_170505b-1.pdf.

- “2021 Planning Summary,” December 12,2020, UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), https://reporting.unhcr.org/sites/default/files/pdfsummaries/GA2021-Yemen-eng.pdf.

- Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Yemen, https://osesgy.unmissions.org.

- “Briefing to the United Nations Security Council: UN Special Envoy for Yemen-Martin Griffiths,” Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Yemen, February 18, 2021, https://osesgy.unmissions.org/briefing-united-nations-security-council.

- “Integrated County Strategy: Yemen,” U.S Department of State, September 10, 2018, https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/ICS-Yemen_UNCLASS_508.pdf

- Nadwa Al-Dawsari, “Running around in circles; How Saudi Arabia is losing its war in Yemen to Iran,” March 3, 2020, Middle East Institute, https://www.mei.edu/publications/running-around-circles-how-saudi-arabia-losing-its-war-yemen-iran

- Alex Emmons,” Secret Report Reveals Saudi incompetence and Widespread use of U.S. Weapons in Yemen,” The Intercept, April 15,2019, https://theintercept.com/2019/04/15/saudi-weapons-yemen-us-france/

- “Press Release on the UN Special Envoy’s recent Meetings,” Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Yemen,” May 5,2021, https://osesgy.unmissions.org/press-release-un-special-envoys-recent-meetings

- “Rethinking Peace in Yemen,” International Crisis Group), July 2, 2020, https://www.crisisgroup.org/middle-east-north-africa/gulf-and-arabian-peninsula/yemen/216-rethinking-peace-yemen.

- “UAE Withdraws Its Troops from Aden, Hands Control to Saudi Arabia,” Reuters, October 30,2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-emirates-military-yemen/uae-withdraws-its-troops-from-aden-hands-control-to-saudi-arabia-idUSKBN1X923A.

- “Emirati Seizure of Balhaf.. Key Challenge Facing Yemeni Gov’t,” Debriefer, December 27, 2020, https://debriefer.net/en/news-22057.html.

- Jon Gambrell, “Mysterious Air Base Being Built on Volcanic Island off Yemen,” Associated Press, May 25, 2021, https://apnews.com/article/mysterious-air-base-volcanic-island-yemen-c8cb2018c07bb5b63e1a43ff706b007b?utm_source=sailthru&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=may25_morning_wire&utm_term=morning%20wire%20subscribers; Joseph Trevithick, “Construction of A Large Runway Suddenly Appears on Highly Strategic Island In the Red Sea,” The Drive, March 10, 2021, https://www.thedrive.com/the-war-zone/39686/construction-of-a-large-runway-suddenly-appears-on-highly-strategic-island-in-the-red-sea.

- Ahmed Nagi, “Five Years of Yemen Conflict Yield Muddled Picture for Saudi Coalition,” Carnegie Middle East Center, March 31, 2020, https://carnegie-mec.org/2020/03/31/five-years-of-yemen-conflict-yield-muddled-picture-for-saudi-coalition-pub-81406; “Emirati Deputy Chief of Staff: I Say It for the Record… We Fought Muslim Brotherhood and Their Fifth Column in Yemen,” Almasdar Online, February 10, 2020, https://almasdaronline.com/articles/177393; “Training Mercenaries.. What Is behind UAE Repeated Announcement to Withdraw Its Forces from Yemen” (in Arabic), Markaz al-Jazeera al-Arabia li al-Al-E’lam, February 17, 2020, https://www.mediacenteraa.com/تدريب-مرتزقة-ماذا-وراء-إعلان-الإمارات/ .

- Ibrahim Jalal, “The UAE May Have Withdrawn from Yemen, but Its Influence Remains Strong,” Middle East Institute, February 25, 2020, https://www.mei.edu/publications/uae-may-have-withdrawn-yemen-its-influence-remains-strong.

- Maggie Michael, “Cracks in Saudi–UAE Coalition Risks New War in Yemen,” Associated Press, September 6,2019, https://apnews.com/article/b1eb5228527043059e40220834cc4b0d.

- Almasdar Online, “We Fought Muslim Brotherhood and Their Fifth Column in Yemen.”

- Adel al-Ahmadi, “Aden Airport Crisis: A Chapter of Conflict between Hadi and UAE,” Alaraby (Arabic), February 13, 2017; https://www.alaraby.co.uk/ أزمة-مطار-عدن-فصل-من-الصراع-بين-هادي-والإمارات; “Yemen Conflict: Southern Separatists Seize Control of Aden,” BBC, August 11, 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-49308199.

- Ibrahim Jalal, “The Riyadh Agreement: Yemen’s New Cabinet and What Remains to Be Done,” The Middle East Institute, February 1, 2021, https://www.mei.edu/publications/riyadh-agreement-yemens-new-cabinet-and-what-remains-be-done.

- Robert Forster, “Independence or Front Lines: Securing Southern Representation in Yemen’s Peace Talks,” Chr. Michelsen Institute, February, 2020, https://journals.uio.no/babylon/article/view/7776/7029.

- “Clashes in Crater Ends with Agreement to Hand over Camp 20 to Al-Asefh Battalions” (in Arabic), Al-Ayyam, March 25, 2020, https://www.alayyam.info/news/859V0S17-V2X82T-B916.

- “Power Struggle among Emirates-Backed Forces Triggers the Situation in Aden” (in Arabic), Al-Araby Al-Jadeed, June 6, 2020, https://www.alaraby.co.uk/صراعات-داخل-القوات-المدعومة-إماراتياً-تؤجج-الوضع-في-عدن; “Explosions Shake Aden and Clashes between Armed Factions” (in Arabic), Aden Al-Ghad, June 18, 2020, https://adengd.net/news/470457/.

- Naseh Shaker, “How UAE Airstrikes on Government Forces Changed Military Map in Aden,” Al-Monitor, September 12, 2019, https://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2019/09/yemen-aden-saudi-uae-rift-talks-separatists-government.html.

- “Shabwani Elite Force Establish Checkpoints in Aden” (in Arabic), Al-Marsad, December 6, 2021, https://www.marsad.news/news/89800.

- “Aden… Thunderbolt Battalions Detain Eighteen Shabwani Elite Force Recruits,” Aden News Agency, April 14,2021, http://www.adennewsagencey.com/87541/.

- The commander cited interference in his job and negligence as his reasons for resigning. “Chief of Shabwani Elite Forces Resigns,” Debriefer, March 29, 2021, https://debriefer.net/en/news-24121.html.

- Adam Baron and Monder Basalma, “The Case of Hadhramaut: Can Local Efforts Transcend Wartime Divides in Yemen?,” The Century Foundation, https://tcf.org/content/report/case-hadhramaut-can-local-efforts-transcend-wartime-divides-yemen/.

- “Yemen’s Fractured South: Aden, Abyan, and Lahij,” Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED), December 18, 2019, https://acleddata.com/2019/12/18/yemens-fractured-south-aden-abyan-and-lahij/.

- “UAE’s Sphere of Influence in Southern Yemen,” ACLED, May 9, 2018, https://acleddata.com/2018/03/09/uaes-sphere-of-influence-in-southern-yemen/.

- “Security Belt Forces… Formal Force of Four Brigades According to a Republican Decree (a Document)” (in Arabic), Aden Time, October 5, 2016, http://aden-tm.net/NDetails.aspx?contid=15198.

- Nadwa Al-Dawsari, “We Lived Days in Hell: Civilian Perspectives on the Conflict in Yemen,” Center for Civilians in Conflict, January 10, 2017, https://civiliansinconflict.org/publications/research/we-lived-in-hell-yemen/.

- Ahmed Al-Haj and Maggie Michael, “Yemen’s Would-Be Model, Aden Plagued by Bombs, Instability,” Associated Press, December 24, 2016, https://apnews.com/2df4bea2fefb4755be6d31051a109b85/yemens-would-be-model-aden-plagued-bombs-instability.

- Ibid.

- Southern resistance leader, interview with the author, May 4, 2020; southern politician, interview with the author, May 5, 2020.

- “Brigadier General Jawas Declares Support for the Southern Transitional Council” (in Arabic), published to YouTube by Faris Al-Ozaibi, August 16, 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=paFXmggSYew.

- “Military Leader Jawas Declares Support for STC’s Self-Administration of the South” (in Arabic), Al-Ayyam, April 27, 2020, https://www.alayyam.info/news/86L4EIUB-3R4GKM-AEF3.

- “Shocking Information and Figures Reveal for the First Time about Twenty-One Colonels Led by a Rebel … and 55 Percent of Military Budget Go to It” (in Arabic), Mareb Press, June 30, 2020, https://marebpress.org/news_details.php?lang=arabic&sid=164949&utm_campaign=nabdapp.com&utm_medium=referral&utm_source=nabdapp.com&ocid=Nabd_App.

- Nadwa Al-Dawsari, “The Popular Committees of Abyan, Yemen: A Necessary Evil or an Opportunity for Security Reforms?,” Middle East Institute, March 5, 2014, https://www.mei.edu/publications/popular-committees-abyan-yemen-necessary-evil-or-opportunity-security-reform.

- The Popular Committees are tribal militias that formed in Abyan in 2011 in response to Ansar al-Sharia threat. They were instrumental in the expulsion of the terrorist group from Abyan in 2012. The Popular Committees had wanted to be incorporated into formal security structures under the Ministry of Defense since 2012, but Hadi’s government failed to bring them into a federal ministry. Eventually, most of the members were recruited into the Security Belt Forces in Abyan.

- Al-Dawsari, “The Popular Committees of Abyan.”

- Abdulatief Al-Sayid, interview with the author, February 2, 2019; Al-Dawsari, “The Popular Committees of Abyan.”

- Prominent southern tribal leader, interview with the author, February 28, 2020; Security Belt officer, Aden, interview with the author, April 2019; resistance leader, interview with the author, May 4, 2020; “Yemen: Al-Qaeda Attacks Military Post, Kills 12,” Anadolu Agency, March 18, 2021, https://www.aa.com.tr/en/africa/yemen-al-qaeda-attacks-military-post-kills-12/2180419.

- “How Mukalla Fell under Aqap and Was Liberated by the Hadhrami Elite Forces” (in Arabic), Almandeb News, April 30, 2020, https://almandeb.news/?p=250119; “Al BAhsani: 30,000 Fighters from Elite Force Protect Hadramout with Emirati Support” (in Arabic), Al-Ayyam, February 27, 2020, https://www.alayyam.info/news/84793MAF-QXRR8S-C069.

- “Letter dated 27 January 2017 from the Panel of Experts on Yemen Addressed to the President of the Security Council,” UN Security Council, January 31, 2017, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/N1700601_0.pdf; ACLED, “Yemen’s Fractured South.”

- These community leaders include “akels”— neighborhood and village elders. Akels are part of Yemen’s traditional security structure. Under Yemeni law, they are considered law enforcement officers. Their job is mostly to facilitate security and some service delivery

- “Yemen’s Houthis Deny U.N. Access to Hodeidah Mills for ‘Safety Reasons’—Sources,” Reuters, April 2, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-yemen-security-un-idUKKCN1RE1IV; “Yemen’s Main Oil Pipeline Blown up Again,” Rigzone, May 24, 2013, https://www.rigzone.com/news/oil_gas/a/126666/Yemens_Main_Oil_Pipeline_Blown_up_Again.

- “The Hodeidah Front,” ACLED, March 15, 2018, https://acleddata.com/2018/03/15/the-hodeidah-front/.

- “News Analysis: Experts Skeptical of Stockholm Truce Deal on Ending Yemen’s War,” Xinhua, September 21, 2019, http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2019-02/21/c_137840180.htm.

- “Who Are the UAE-Backed Forces Fighting on the Western Front in Yemen?,” July 20, 2018, https://acleddata.com/2018/07/20/who-are-the-uae-backed-forces-fighting-on-the-western-front-in-yemen/.

- “Serah—The Joint Forces on the Western Coast in Yemen,” Al-Sahel Al-Gharbi, February 12, 2021, https://alsahil.net/news6960.html.

- “After Announcing a Joint Command in the West Coast…Will Saleh Forces Work on Behalf of UAE?,” Almashhad Alyemeni, July 10, 2019, https://www.almashhad-alyemeni.com/138483.

- Officer of the Joint Forces, interview with the author, July 14, 2020; Yemeni journalist, interview with the author, July 14, 2020.

- Senior member of the Al-Zaraneeq Brigade, interview with the author, July 16, 2020; Senior member of the Tihama Brigades, interview with the author, July 15, 2020.

- Tihama Coast analyst Ibrahim Jalal, interview with the author, May 21, 2021.

- “Yemeni Regime Accuses Hamid Al-Ahmar of Trying to Assassinate President Saleh,” Jamestown Foundation, August 19,2011, https://www.refworld.org/docid/4e5218642.html

- “From Mocha, Tareq Saleh Declares a Political Entity as a Cover for His Forces in the West Coast” (in Arabic), Almasdar Online, March 25, 2021, https://almasdaronline.com/articles/219623; Interview with the spokesman for the Joint Forces, July 14, 2020

- A Joint Force affiliate, interview with the author, July 6, 2020.

- “Saleh Is Looking for a Place in the Anticipated Power Share in Yemen,” (in Arabic), Al-Araby Al-Jadeed, March 25, 2021, https://www.alaraby.co.uk/politics/طارق-صالح-يبحث-عن-موطئ-قدم-في-خارطة-المحاصصة-المرتقبة-باليمن.

- Local researcher, interview with the author, July 9, 2020.

- Spokesman for the Joint Forces, interview.

- Gareth Browne, “Who Are the Yemeni Ground Forces Fighting in Hodeida?,” The National, June 14, 2018, https://www.thenational.ae/world/mena/who-are-the-yemeni-ground-forces-fighting-in-hodeidah-1.740197.

- Valentin d’Hauthuille, “Who Are the UAE-backed Forces Fighting on the Western Front in Yemen?” ACLED, July 20, 2018, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/acleddata.com-Who%20are%20the%20UAE-backed%20Forces%20Fighting%20on%20the%20Western%20Front%20in%20Yemen.pdf.

- Resistance leader from Aden, interview with the author, May 4, 2020.

- “Sources: Giants Brigades withdraw from the West Coast on UAE orders to participate in potential clashes with Yemeni government” (in Arabic), published to YouTube by Yemen Shabab TV channel, October 6, 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zBb0K_NMa1Y.

- “Tihama Movement between Houthi’s Fire and Saleh’s Revenge,” Alhodeidah Times (undated) http://www.hodeidahpress.net/mobile/detail.php?sid=130.

- Interview with a journalist from the west coast, August 10, 2020

- The imams were the rulers of Yemen under the imamate,. The name “Tihama Brigades”’ symbolizes the resurgence of a Tihama force that wants to restore the dignity of Tihamis and authority over their land. See “Tihama Went through Catastrophes at the Hands of Imam Yehya and His Son Ahmed and Was Marginalized during Saleh” (in Arabic), Mareb Press, September 29,2013, https://marebpress.net/news_details.php?sid=60273.

- Journalist from the West coast, interview with the author, August 10, 2020.

- Local journalist, interview with the author, July 9, 2020.

- Senior member of the Tihama National Council, interview with the author, July 16, 2020.

- “Briefing to United Nations Security Council by the Special Envoy for Yemen—Martin Griffiths,” Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Yemen, May 12, 2021, https://osesgy.unmissions.org/briefing-united-nations-security-council-special-envoy-yemen-%E2%80%93-martin-griffiths-3.

- Tom Miles, “Southern Yemenis Warn Exclusion from U.N. Peace Talks Could Trigger New Conflict,” March 1, 2019, hhttps://www.reuters.com/article/us-yemen-security-stc-idUSKCN1QI5HJ.

- “Tareq Saleh Stresses: Stockholm Agreement and the Houthis Are on Their Last Breath” (in Arabic), Free Yemen Eye, May 25, 2020.

- Mazen Al-Shaibani, “Describing It as a Conspiracy, Tareq Saleh Calls upon Yemen’s President to Withdraw from the Stockholm Agreement” (in Arabic), Almashhad Alyemeni, January 24, 2020, https://www.almashhad-alyemeni.com/156222.

- Spokesman for the Joint Forces, interview; Tihama Brigades member, interview with the author, July 18, 2020.

- Two senior members of the Joint Forces, interviews with the author, July 14, 2020, and July 6, 2020.